Note: This is the 3rd and final part of a 3-part Effective Communication in Conflict for Higher Education Leaders series. As a leader in higher education, you will undoubtedly face your fair share of conflict situations and critical conversations throughout your career. Your ability to handle these emotionally charged scenarios can make or break your career, which is why I’ve devoted an in-depth, three-part series to helping you succeed in handling critical conversations and managing conflict. If you missed the previous installments in this series, you can read part one here and part two here.

Note: This is the 3rd and final part of a 3-part Effective Communication in Conflict for Higher Education Leaders series. As a leader in higher education, you will undoubtedly face your fair share of conflict situations and critical conversations throughout your career. Your ability to handle these emotionally charged scenarios can make or break your career, which is why I’ve devoted an in-depth, three-part series to helping you succeed in handling critical conversations and managing conflict. If you missed the previous installments in this series, you can read part one here and part two here.

I’ve been an Executive Coach for higher education leaders for more than twenty years and I developed and teach a program called Effective Communications: How to Approach Critical Conversations and Conflict Situations, which is designed for higher education leaders who face difficult situations that are often unique to educational environments.

This series introduces you to the fundamentals of the program I teach and provides insights into how you can become more adept as a leader facing conflict situations.

In part one of this series, I discussed the critical role your Emotional Intelligence plays in your success in conflict.

In part two of this series, I walked you through a four-step model that helps you approach critical conversations and conflict situations successfully.

In this third and final installment in this series, I introduce you to an actual case study, and show you how the four-step model works in a higher education scenario where conflict was inevitable and critical conversations were required.

A Quick Review of the Four-Step Approach to Handling Conflict in Critical Conversations as a Leader in Higher Education

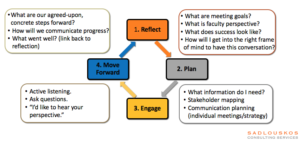

As you may recall from part two of this series, the four key steps in handling conflict include:

- Reflect– Prepare yourself for what’s ahead and think through the outcomes that you want to achieve, the needs others may have, and mentally prepare yourself for the difficult conversation you anticipate.

- Plan– Create a plan for how you intend to handle the actual conversation where you address the conflict with the other party/parties involved.

- Engage– Engage the person or people you’re conversing with, extending compassion, respect, and an open mind.

- Move Forward– Focus on how the parties involved will move forward together. The goal of this step is to formulate a clear, complete vision for what is to happen next.

Now that you have a firm grasp on the four-step approach to handling conflict and critical conversations, I want to introduce you to a new tool that you’re sure to find invaluable: Stakeholder Mapping.

Understanding a Stakeholder’s Level of Interest and Influence

Before you engage in any conflict-prone confrontation or conversation, it’s best to understand what each person involved in the conflict (each stakeholder) has at stake. I recommend using Stakeholder Mapping to do this (see chart below).

In any conflict situation, each person involved may have varying degrees of both interest and influence regarding the outcome of the situation.

The people involved in the conflict may be highly invested (i.e., highly interested) in the outcome, or have a low interest in how the situation plays out. Also, each person involved might have a high degree of influence over what happens or a low degree of influence.

As you can see from the stakeholder map I’ve provided here, there are four different interest/influence combinations where each stakeholder in the conflict could land, and there’s a different situational management tactic that leaders should employ for each circumstance.

1 Monitor: When a stakeholder has both low influence and low interest in how a conflict situation plays out, the best tactic for the leader to employ is simply to monitor the situation. A leader needs to keep an eye on the individual’s needs, wants, and interests in case they should change, but there is no need to be overly focused or concerned about this stakeholder’s reactions. The person who falls in this quadrant simply isn’t all that involved or interested in the outcome.

2 Inform: When a stakeholder has relatively low influence regarding the matter at hand, but is highly interested in the matter, the leader’s job is to keep this person in the communication loop. When stakeholders with low influence but high interest are kept highly informed, they feel more comfortable and may be more inclined to offer support rather than resistance.

3 Consult: When a stakeholder involved in the conflict or critical situation has low interest but high influence, a leader’s best bet is to consult with this stakeholder. Influential stakeholders can sway others’ opinions and impact a leader’s future career success, so it’s best to take great care to consult with influential stakeholders throughout the process.

4 Involve: When a stakeholder in the conflict situation has both a high interest in the outcome and high influence over the outcome, that person must be kept highly involved from day one. Involving high-interest, high-influence stakeholders helps improve the odds that there won’t be extreme resistance to initiatives that are proposed. When this stakeholder is supportive of an initiative, their influence can help get others on board. Of the four types of stakeholders, those with high influence and high interest are the most important to keep highly involved and highly satisfied.

Case Study: Gaining Consensus on a Formal Policy Addressing Faculty Advisor/PhD Student Relationship Expectations

The best way to fully appreciate the steps I’ve outlined for managing conflict and critical situations is to walk you through a case study.

In this case study, Sara is the is the new Vice Chair of her Science Department. The university’s academic leadership has encouraged individual colleges to develop guidelines for setting expectations for advisor-student relationships that best supports students to succeed in their PhD programs.

Advisor-student relationships had not traditionally been governed or guided by such a formalized process, as such there is much debate about instituting this change. To many, the quality of advising is viewed as uneven. Sara has inherited this policy initiative from her predecessor, who was recently fired for being divisive and ineffective.

Sara recognizes that taking on this initiative and gaining consensus on the guidelines will be highly political yet necessary in order to set expectations for PhD students in how advisors can best be leveraged. This new advisory approach will require buy-in from the faculty committee.

Sara has done her due diligence in developing a new policy document with input from junior faculty as well as long-time tenured faculty. She knows the ideas for this document will make a meaningful impact and is intent on getting the substantial change implemented, but she knows she cannot do it alone.

Sara suspects that some of the members will not willingly embrace the proposed changes and wants to take great care with how she introduces the draft policy document to the committee and how she interacts with those involved.

Though new to her role as Vice Chair, Sara is a savvy leader and understands that her ability to influence the committee on this first major change initiative could impact her success as a leader for years to come. The stakes are sky-high for Sara.

Before speaking with anyone, Sara begins her policy adoption strategy with a stakeholder mapping process.

Identify Stakeholders and Categorize Them as Resistant, Supportive, or Neutral

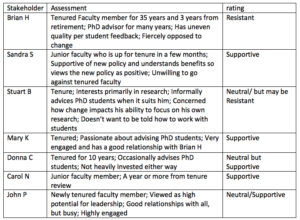

In addition to Sara, there are seven stakeholders on the committee. Sara did her homework and categorized each based on their level of interest and influence on the acceptance process. Sara assigned each stakeholder a rating: resistant, supportive, or neutral.

The stakeholders and their anticipated supportiveness/resistance levels are as follows:

As you can see from the chart, Sara knows she is entering this situation with one known resistant stakeholder who has both high interest and high influence over the outcome: Brian.

The other likely resistant stakeholder is Stuart, a tenured researcher who informally advises students on an ad hoc basis. Stuart will resist any change effort that has even a remote chance of impacting him. Stuart is wary of all changes.

Mary is one of Sara’s most powerful allies in getting this change adopted. Mary is a tenured professor who not only supports Sara’s ideas, Mary also has an excellent working relationship with Brian, the initiative’s most ardent resister. Sara knows Mary’s relationship with Brian could be useful in helping smooth the path for adopting the change.

Sara has two more supportive committee members in Carol and Sandra, though neither are tenured, which means they have less influence than their resistant counterparts.

There is another supportive yet neutral person on the committee, Donna. Although tenured and regularly advises students, Donna’s overall interest in the outcome is low.

Finally, there’s the completely neutral John, who recently received tenure and has great relationships and growing influence with other committee members but isn’t particularly invested in the outcome of this policy initiative because he’s busy.

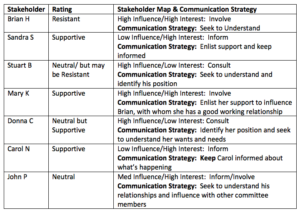

Stakeholder Mapping & Communication Strategy

Based on Sara’s review of the various committee members’ level of interest and influence, as well as their likelihood of being resistant, supportive or neutral, Sara developed the following communication plan to address each committee member’s unique perspective and needs.

Pre-Commmittee Meeting Communication Plan

Sara knows better than to go into this politically charged committee meeting without doing some “pre-meeting” relationship building with each of the committee members. Sara’s still new to her role and she needs to give each committee member a chance to get to know her better and understand her leadership style, what she’s doing, and why she’s doing it.

Most of all, Sara needs for the committee to understand that she is open-minded, caring, and wants only the best for the faculty and students. In her predecessor’s tenure, game-playing and political maneuvering were the norm; Sara wants these divisive tactics to come to an end under her leadership.

Sara also knows that she only has a superficial idea of each stakeholder’s interests and needs; she must dig deeper and that can’t be done in a group conversation.

Sara is highly Emotionally Intelligent, and her goal is to make each committee member feel heard and feel valued. She understands that the relationship-building strategies that work with one person will not work with all; each committee member has his or her own needs, issues, and perspectives, and those must be acknowledged and addressed.

Sara schedules a one-on-one meeting with each committee member prior to the main group meeting where final decisions about the change initiatives will be made.

Mitigating Conflict in Critical Conversations: Pre-Committee Meetings Using the Four-Step Process

Much of the work for setting the stage to any successful policy adoption in higher education is done prior to committee meetings. Strong one-on-one relationships create the fertile ground necessary for new initiatives to take root and grow.

In each of her one-on-one meetings, Sara employs the four-step conflict management and critical conversations process: 1) Reflect, 2) Plan, 3) Engage, 4) Move Forward.

Sara begins the one-on-one meetings with Mary, a tenured professor who is passionate about the advisory relationship and who is supportive of this policy initiative.

Since Mary is such a strong supporter of the policy initiative while also being extremely influential with other tenured professors, Sara’s key objective is to enlist Mary to influence Brian, the most ardent resistor of change and one of Mary’s closest colleagues. Sara has no trouble getting Mary on board to help gain buy-in from Brian.

Sara continues to meet one-on-one with each committee member, working her way down the list from most supportive to most resistant.

With Carol, a junior faculty member who is still a year or two away from tenure consideration, Sara simply keeps Carol in the loop, ensuring that Carol’s enthusiasm for this policy initiative continues. Sara makes Carol feel heard and valued, which will bear fruit throughout their entire relationship working together.

When Sara meets with Sandra, another junior faculty member who’s in the queue for tenure consideration in the next few months, the dynamic between the two is strong. Sara’s goal entering the meeting was to keep Sandra informed and enlist her support in spreading positive feedback about the proposed changes. The meeting is a success.

Next, Sara meets individually with Donna and John, both of whom are basically neutral regarding the proposed changes.

Not surprisingly, Donna, a tenured professor who is not all that engaged but generally supportive of Sara as Vice Chair, agrees to support the proposed changes. Donna commits to voicing her support during the committee meeting which will enhance the likelihood of the policy moving forward in the approval process.

John is a recently tenured faculty and viewed as a high potential leader. All faculty, both tenured and untenured, think very highly of John. He is also very respected by PhD students.

John has remained neutral largely because his plate is so full. He has been appointed to many committees, has recently started advising PhD students, and is busy with his own research and teaching. Although John is committed to being neutral to avoid the politics, he agrees to being supportive during the meeting. Sara and John’s working relationship is bolstered by the one-on-one connection, the exact outcome Sara needed.

John may not be an enthusiastic support of the policy initiative, but he’s not a barrier to the change either. Even better, his opinion of Sara is growing, and he’s sure to share that opinion with the other committee members, with whom his opinion matters greatly.

Sara’s next meeting is with Stuart. Sara’s goal in meeting with Stuart, the tenured researcher who is known for being anti-change in general, is to get Stuart to understand that he will be minimally impacted by the proposed changes and that Sara’s intentions are truly for the betterment of the department overall and not a political ploy.

Sara prepares for Stuart to be skeptical, which he is. In the meeting, Sara allows Stuart ample time to voice his thoughts and ideas in their one-on-one meeting; Stuart needs to be heard and he has a lot to say, much of which is off-topic, but Sara knows that listening to Stuart will work wonders for their ongoing relationship. The meeting is a success; Stuart agrees to remain neutral on the change rather than resist it.

Sara deliberately saves Brian as her last one-on-one meeting. With Brian, the tenured faculty member who is three years from retirement and who is not particularly engaged but fiercely opposed to change, Sara knows she’s facing an uphill battle.

Sara’s main plan for Brian was to get others in the department to influence him before Sara and Brian’s one-on-one meeting. The strategy worked: Brian’s heard many supportive comments, especially from Carol and John, both of whom he highly respects.

Still, Brian is a tough case to crack. He’s open to listening to Sara in their meeting because his colleagues spoke so highly of her, and then dominates the conversation on all the reasons they shouldn’t change. He remains fiercely opposed to change of any kind.

Throughout their conversation, Sara employs active listening, asks questions, and shares why she’s presenting the policy change to the committee. Sara assures Brian she will consider his perspective.

Brian is stuck in his ways and isn’t going to change; Sara suspected this in planning for the meeting, but their face-to-face interaction confirms this fact. Still, in all likelihood Sara will be working with Brian for three more years until Brian retires and she doesn’t want those years to be adversarial. They agree that moving forward they’ll have monthly one-on-one meetings where they can address issues that are important to each of them and to the team as well.

The Committee Meeting

The climate of the group meeting is genuinely respectful. Everyone arrives with clear expectations of what is happening and understands how the proposed changes will impact them.

Brian, who is still resistant to the change, offers some modest changes to the proposed policy initiative, and the committee agrees to implement his suggestions. Brian still doesn’t want to change, but since his suggestions were favorably considered, he is far less likely to be proactively disruptive as the changes are implemented.

Sara’s work in the pre-committee meetings ensured she had the support she needed to vote in adopting a formal advising policy for the department.

Sara’s adept handling of the conflict situation and the critical conversations demonstrated that she is an insightful, thoughtful, caring, visionary leader. Her reputation was bolstered tenfold by how adeptly she handled this situation.

Had Sara not understood the principles of conflict management and critical conversations, this meeting could have been a disaster and the change initiative would have failed miserably. Her careful and strategic relationship-building beforehand made the entire process less confrontational and more successful overall.

Conflict In Critical Conversations Summary

Knowing how to handle conflict situations, difficult people, and critical conversations are all crucial skills for all higher education leaders. You will face conflict. You will encounter difficult people. You must proactively conduct critical conversations, otherwise you’ll find that misunderstandings and conflict will escalate.

***

As I introduced in Emotional Intelligence and Conflict: Vital Lessons for Higher Education Leaders, building your Emotional Intelligence is the first and most important step to becoming an effective conflict manager and critical conversations expert. I work with higher education executives to build these skills all the time, in one-on-one coaching sessions and in group training sessions where I teach the essentials of strong Emotional Intelligence. Be sure to contact me if you or your team needs help in this area.

In part two of this series, the 4 Steps to Approaching Critical Conversations: A Roadmap for Higher Education Leaders, I walked you through the 4-step model that helps you manage any conflict situation more effectively.

Finally, in the case study presented here, you saw how the four steps (reflect, plan, engage, and move forward) along with stakeholder mapping work together to help higher education leaders prepare for and conduct critical conversations and address conflict situations successfully.

Thank you for following this series. I know you’re a busy leader and your higher education responsibilities demand a lot from you. I also know that the skills you learned here will help you be seen as highly respected and visionary leader, which will in turn fuel your success throughout your entire career.

If you need any further help with building your Emotional Intelligence or with developing conflict management and communication skills for you or your team, please contact me at Sadlouskos Consulting Services. I’d be happy to help you.

****

If you’d like to read more about Emotional Intelligence, a critical component in developing the effective communication skills, I recommend Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ, written by Daniel Goleman which he published in 1995 along with four highly popular articles in the Harvard Business Review.